How we use the GV design critique to find problems before they cost you money

I usually explain it to clients with this story: A bunch of admirals was asked to plan out a military campaign for a written exam. They were all accomplished strategists, but when confronted with a blank piece of paper, they all failed the test. So the navy paired them off, allowing each team to share notes. Instantly they started acing the test. All it took was that little bit of outside perspective, all of a sudden you see a bigger picture.

That’s what the Google Ventures design critique does for us.

We stay pretty close to Google Ventures’ guide on how to run a design critique. We start with a small team, focused on a specific part of the design, fitted with the following set of rules:

- Designers can’t pitch their designs, because it robs us of our fresh set of eyes

- Each reviewer will spend up to 10 minutes reviewing the design alone before providing feedback

- Both positive and negative feedback must be given

- No designing in the meeting — identify the problems, don’t create the solutions

We've got to fall in love with the problem, that’s our job as designers. But it’s hard to see the problems in your own work. The GV design critique is a chance to say “I'm a designer, I have questions,” so a cross-disciplinary team can help you quickly uncover all the potential problems hiding in your design. We apply the Google Ventures process to our website design critiques, our graphic design critiques, our app design critiques, our research critiques whatever it is that we’re building because it’s versatile enough to get us honest answers every time.

The GV design critique creates a safe, structured place for discussion and disagreement. As people, we have a tendency to try to soften the blows when we’re discussing problems with a design. But as a team, we owe each other — and our clients — more than that. Without finding those problems, it's hard for a design to ever be successful.

Will, our senior UX strategist, says outright that he thinks the critique process is the most valuable thing we do for our clients. Here’s how we use the GV design review to save our clients money:

Coalescing a team around a client’s goals — fast

When we talk about the cost of a project, we're usually talking about the results. But so much of that cost happens at the beginning of a project. It’s very difficult to get a team to have shared understanding of a client’s needs and business objectives, and to understand that client’s users. If you can get everyone to do that very quickly and very clearly, it reduces the cost for the entire project. By locking our team in a room together, everyone is able to combine their individual view of the client to get a precise collective picture. It saves us each from having to do hours of research or shipping a poor experience for your users, and it ensures we’re all working toward the same goals, rather than from our own siloed views.

Empowering everyone to have a useful voice in the design

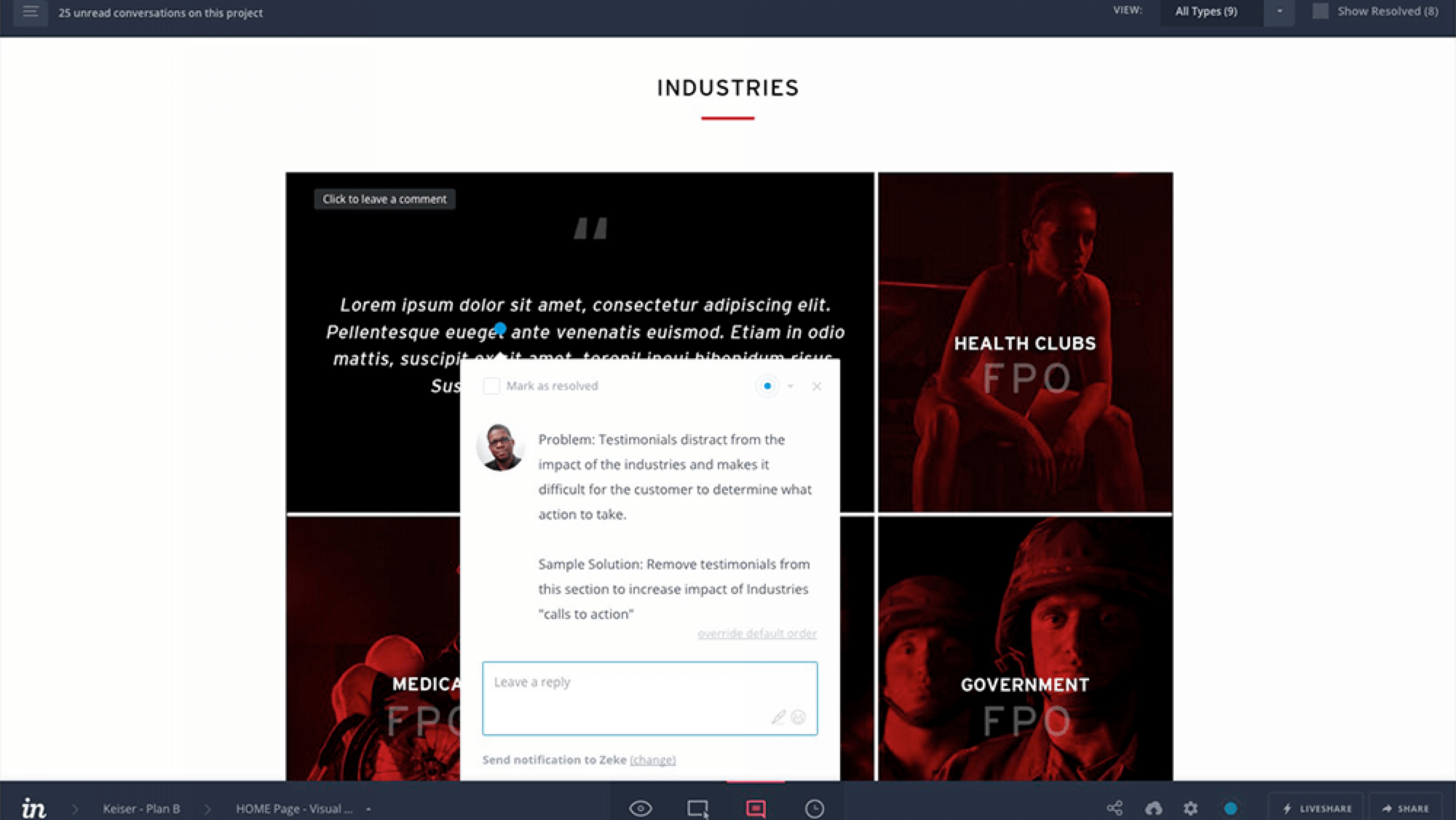

When we first implemented this process, Robin Dunlop, who does our QA work, actually began to talk to me differently as a designer. He stopped trying to offer me solutions and started telling me, "Hey Zeke, here's a problem, I just want you to understand that this is a problem and it's yours to solve." We instantly went from wasting 30 minutes trying to figure out the problem each time, to having a five-minute conversation that captured the issue.

In the room, we keep the design critique focused on the problem. There’s no designing in the room, which can be a real challenge for some people. We explain that you can’t say to move a button, but you should instead say that you’re worried a button is getting lost and you want it to have more weight in the visual hierarchy. How that happens is a designer’s problem to solve. In some cases the problem is too complicated to discuss without a solution. So the facilitator’s job is to have them state the solution, and then work backwards into the problem. And then the problem is still what we're capturing.

To make sure everyone is providing their honest opinions, we have each person spend five to 10 minutes alone with the design, jotting down their thoughts. That way we avoid groupthink, where everyone responds to the first idea instead of voicing their honest reactions. It also gives introverts the ability to collect their thoughts first, so they’re more comfortable voicing them. When an extrovert brings up a topic, the quieter people in the room get an opportunity to feel validated, because they already have that in their notebooks. And because we're strong facilitators, most of the time we're looking for people who are being quiet and seek out their participation.

Collecting diverse perspectives that keep us from relying on assumptions

For each GV design critique, we typically invite the entire project team, plus an outsider. The outsider is there to test our assumptions. Bringing in someone with a fresh set of eyes usually gets to some questions that we just weren't thinking of. Oftentimes we can’t see potential problems because we know the brand and the product line in a way that blinds us.

During one of our critiques for Dickson, an outside project manager asked “What is DicksonOne?” We were so close to the project and so familiar with the DicksonOne — one of the client’s most popular products — that we were unable to see we hadn’t explained it in a way newcomers could understand.

Letting developers steer us away from complexity

Bringing developers into the design phase gives them a chance to see what’s coming down the pipe for them. It also gives designers a chance to get feedback from developers about things that are more complex than they need to be. A lot of times you end up refining things, until we end up with the best way we can make this solution. Clients sometimes worry when we reduce a feature from a development standpoint, but cutting back the scope makes it much more rock-solid. When it’s a smaller feature, you can cover a lot of the edge cases much easier. You end up with a much more polished interaction because the scope is smaller.

Forcing designers to work on proven problems, not pet solutions

My hatred or love of a particular color is very hard to translate into a problem. With the GV design review, it's difficult for anyone to go, 'Man, I just really love that blue and yellow combination.' Because if it becomes a problem, then it's a problem and we have to solve it. But I get to be very creative in how I solve it.

The same is true for designers who are stuck on a particular interaction. Sometimes you fall in love with a form, but that form isn't helping the user purchase the thing they want to buy. So we try to keep ourselves very honest. Are we actually solving the problem? Knowing you’ll have to explain yourself in the design critique keeps you from making selfish choices.

Keeping ourselves honest about the scope

Designers want to create the best possible solution — even when that’s not what the client needs right now. A design critique gives us a chance to make sure our design is best meeting our client’s current customers and budget, not envisioning a future state of the product that may never get built. That way we can respect time and budget with what we're designing. Designers coming out of a critique should have a better sense of what action items are within scope, so they’re not spending a lot of time on functionality that might never see the light of day.

Identifying the good solutions at the start

The negative feedback in a design critique is a crucial way for us to prevent unnecessary work, but the positive feedback lets us make sure we’re not tossing any work that’s already solving the problem. I've had designs where I've gone through about eight revisions and I've lost something important. And you're just never going to get it back. That’s why we ask design critique participants to talk about the positive along with the negative. What happens in critiques oftentimes is people lose sight of what's working, and if you throw the piece that's working out the window, then you've lost something incredibly important. So we make sure everybody highlights what's working before we even start talking about what's not. It reduces the time, which saves money, and it also reduces the amount of effort a designer spends. Instead of reworking an entire design, they can just focus on the piece that isn’t working its best. Which is awesome.

Clients who are unfamiliar with design critiques sometimes balk when they see a one-hour meeting that has five people billing in it. But the most expensive thing you can do is build the wrong feature. That’s why it’s so necessary to hold a design review after every few design sprints. Gathering perspectives makes the product better, which supports a client’s business objectives in the long run. But it’s the short run value that really helps us all. When five people spending one hour can keep one person from wasting 20 hours, that’s an easy decision to make.

Published in Design

Let's shape your insights into experience-led data products together.